It takes but a moment to cast a fleeting glimpse into light’s depths and dalliances, to achieve a brief refocusing on suggested form, to recognise the suggestion of permanence in the impermanence of shadow and shade. Or maybe it takes more than that; an altered perspective perhaps, a receptiveness to other ways of seeing.

Whatever the key, whatever the impetus, the experience richly rewards the effort. An eye trained to look beyond and below perceives a world of suggested space and hidden meaning, not least a translation of corporeal into insubstantial art. Works viewed thus gift freely an understanding of their latent moods, their concealed energies and tensions. They reveal the warp and weft of their inner meaning, one not necessarily invested by their creator, but just as freely nurtured by our imagination.

And so to China …

The Heavenly Horse stands proudly, lips curled, nostrils flared. See the shaded wake of one hoof trailing through light. In that wake we hear the shadow bell toll, and see in its impermanence a silhouette of its physical brothers displayed close by. Shade shifts to substance; archaic bronze stands ready to receive the mallet’s blow. Now look again. Look at the suggestion of shape, and see sister to the stupa held aloft in the Heavenly Guardian’s hand. This proud creature does more than stand inertly, but in the shade it casts leads us to a better understanding of distant ritual and belief.

The Heavenly Horse stands proudly, lips curled, nostrils flared. See the shaded wake of one hoof trailing through light. In that wake we hear the shadow bell toll, and see in its impermanence a silhouette of its physical brothers displayed close by. Shade shifts to substance; archaic bronze stands ready to receive the mallet’s blow. Now look again. Look at the suggestion of shape, and see sister to the stupa held aloft in the Heavenly Guardian’s hand. This proud creature does more than stand inertly, but in the shade it casts leads us to a better understanding of distant ritual and belief.

Now turn. Neither sun nor moon tracks the heavens of these spaces, and yet, bathed in the artificiality of engineered light, these galleries offer a life of sorts to those receptive to seeing it. A dozen horses and riders stand silent sentinel, gripped in ceramic inertia, as if still constrained by the ancient moulds that once gave them form. No hint of movement gives clue to their hidden purpose, or so it seems. But look beyond and recognise what shadow invests; movement and living presence, the once inert now blessed with an ethereal spirit, a living, animated, approaching presence. We strain our ears to validate the conceit; to detect the muffled approach we think we see. Hoof treading softly on ground, on air, on light itself.

Now turn. Neither sun nor moon tracks the heavens of these spaces, and yet, bathed in the artificiality of engineered light, these galleries offer a life of sorts to those receptive to seeing it. A dozen horses and riders stand silent sentinel, gripped in ceramic inertia, as if still constrained by the ancient moulds that once gave them form. No hint of movement gives clue to their hidden purpose, or so it seems. But look beyond and recognise what shadow invests; movement and living presence, the once inert now blessed with an ethereal spirit, a living, animated, approaching presence. We strain our ears to validate the conceit; to detect the muffled approach we think we see. Hoof treading softly on ground, on air, on light itself.

And then to Northern Europe …

Here light and shade do more than gift life to the inanimate. Here, through light or the lack of it, we shift time. We see forwards from the perspective of centuries long gone, to years more recently passed, and days we may have known ourselves. We see, through a curious alchemy of reflection, projection and starvation, light’s ability to suggest new meaning, to transcend style. Styles deemed incongruous by period and tradition, here now invested in a single work; artists separated by geography and time, united in curious kinship.

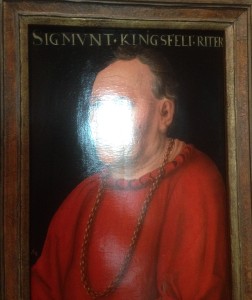

I step to the left, let through the natural light from Naples, and Lucas Cranach’s portrait mutates and transforms before me. The patrician’s features, once so benign, surrender now to the violence of light. Cranach’s subtle palette is brutally vanquished by sterile illumination. And at this instant two voices converse, two styles merge. Francis Bacon tears a fissure across the centuries, and through it daubs a screaming white smear across Cranach’s incredulous face.

I step to the left, let through the natural light from Naples, and Lucas Cranach’s portrait mutates and transforms before me. The patrician’s features, once so benign, surrender now to the violence of light. Cranach’s subtle palette is brutally vanquished by sterile illumination. And at this instant two voices converse, two styles merge. Francis Bacon tears a fissure across the centuries, and through it daubs a screaming white smear across Cranach’s incredulous face.

And whilst we’re at it, let’s effect another introduction. Two souls born centuries apart; two souls born to similar afflictions, each consumed by the desire, not least the compulsion, to reveal nature from nature. Him? His chosen medium is wood. Her? Stone and plaster, but wood and metal too. His hands guided chisel and mallet, hers too. His fingers caressed limewood, hers marble and bronze. His language, archaic and foreign; hers, northern accented, modern. But shadow reveals to us the lie. Shadow proves the commonality of their tongue. Shadow reveals in its depths the universality of their vision, the subtlety of their shared craft. In shaping the Female Saint’s drapery Tilman Riemenschneider pre-empts Barbara Hepworth’s sinuous curves by centuries, and in so doing reveals their true relationship; brother and sister in the sculptor’s art.

And whilst we’re at it, let’s effect another introduction. Two souls born centuries apart; two souls born to similar afflictions, each consumed by the desire, not least the compulsion, to reveal nature from nature. Him? His chosen medium is wood. Her? Stone and plaster, but wood and metal too. His hands guided chisel and mallet, hers too. His fingers caressed limewood, hers marble and bronze. His language, archaic and foreign; hers, northern accented, modern. But shadow reveals to us the lie. Shadow proves the commonality of their tongue. Shadow reveals in its depths the universality of their vision, the subtlety of their shared craft. In shaping the Female Saint’s drapery Tilman Riemenschneider pre-empts Barbara Hepworth’s sinuous curves by centuries, and in so doing reveals their true relationship; brother and sister in the sculptor’s art.

In the next-door room a curious illusion awaits. Shift your eye for a second. Shift it from the Madonna, shift it from the frame; train it on the colour-drenched wall alongside. And where then? Where to focus now? Ignore the Perspex surround that aims to confuse the eye, but consider the perverse dimensions of its shadow. In alarming contradiction it both plumbs the depth of colour, down to the ruddy pits of deepest red, and yet thrusts forward the image it holds in its embrace, urging us to step back and admire. In an alarming shift of dimension it both threatens to consume and propel the unwitting image. And our dilemma? Knowing how best to react; intervention or observation? I step back, look on, then walk away.

In the next-door room a curious illusion awaits. Shift your eye for a second. Shift it from the Madonna, shift it from the frame; train it on the colour-drenched wall alongside. And where then? Where to focus now? Ignore the Perspex surround that aims to confuse the eye, but consider the perverse dimensions of its shadow. In alarming contradiction it both plumbs the depth of colour, down to the ruddy pits of deepest red, and yet thrusts forward the image it holds in its embrace, urging us to step back and admire. In an alarming shift of dimension it both threatens to consume and propel the unwitting image. And our dilemma? Knowing how best to react; intervention or observation? I step back, look on, then walk away.

I walk back to my memory of recent exhibitions. Back to the memory of latticed light and shade. Back to where illumination braided shadow with radiance. Back to that place where the tide of light flowed out and drew me in. Back to the galleries, back to the shade and shine. Back to alternative ways of seeing.

Images: All images are courtesy and copyright of Compton Verney.