Rummage is a satisfying word. I like its nautical origins, its debt to the Old French arrumage and Middle Dutch ruim. I love the connotations of “the arranging of casks in the hold of a vessel” or “miscellaneous articles, lumber, rubbish etc.”, and not least “bustle, commotion, turmoil” or “fish out or dig up by searching”.

Rummage is a satisfying word. I like its nautical origins, its debt to the Old French arrumage and Middle Dutch ruim. I love the connotations of “the arranging of casks in the hold of a vessel” or “miscellaneous articles, lumber, rubbish etc.”, and not least “bustle, commotion, turmoil” or “fish out or dig up by searching”.

In my study I have an old bureau, inherited from my Grandparents. The top section is compartmentalized, an ideal place for small books, for the ordering of miscellaneous articles; no lumber or rubbish here. When I write at the down-turned leaf, all polished oak and rich warm patina, I scan the spines and fish out recollections and more intimate significances. Here stands The Dairyman’s Daughter, no taller than my thumb, bound in black calf, a wedding gift from my In-Laws, dairy farmers in Somerset. And here A History of Primrose Prettyface adorned with Bewick’s charmingly naive wood engravings, an early discovery from my York rummaging days.

As time went by more old volumes displaced the little books of my childhood and youth, and so the modest collection of Observer’s books were relegated to some other bookcase, some other hold. Reluctant evictees of the now-crowded bureau; all bookish bustle, commotion and turmoil.

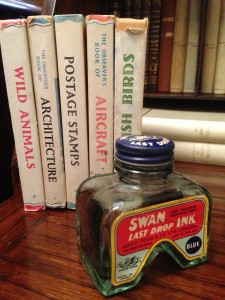

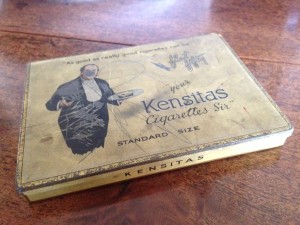

Last week, for no other reason than to rummage, I opened the top drawer of the bureau. In a strangely Carter-esque way I peered in at a moment of myself, at a selective though rich layer of a previous me. I held the small bottle in my hand. Swan Last Drop Ink read the label; the base of the bottle ingeniously forked to ease the retrieval of the “last drop”. Beneath it, in the lower strata, from an earlier timeline, a slim flat Kensitas cigarette tin. I opened the lid and found inside a collection of Brooke Bond Tea cards on The History of the Motor Car – No. 36 the 1934 Lagonda 4 ½ litre saloon, No. 24 the 1924 Morris Cowley Bullnose. I closed the lid.

An image of a waiter is printed on the lid, resplendent in white tie and tails, holding out a tray on which rests the tin of cigarettes “Your Kensitas Cigarettes Sir” he says benevolently. And then the connection was forged, from bottle to tin to books. A long-repressed spike from my past compelled me to reunite the three. I ran to my daughter’s bedroom, retrieved from her bookcase five small volumes, and placed them alongside the bottle and tin.

An image of a waiter is printed on the lid, resplendent in white tie and tails, holding out a tray on which rests the tin of cigarettes “Your Kensitas Cigarettes Sir” he says benevolently. And then the connection was forged, from bottle to tin to books. A long-repressed spike from my past compelled me to reunite the three. I ran to my daughter’s bedroom, retrieved from her bookcase five small volumes, and placed them alongside the bottle and tin.

I remember the act distinctly, though not the trigger. I remember that day (was it day?), when youthful rage got the better of me. The bottle, it would seem, was the innocent partner, a receptacle for the ink, a dependable filling station for the fountain pen. Then it struck, that long forgotten impulse to harm, to destroy, to mindlessly scar even the fondest belongings. The pen dealt the first blow. In a moment of uncontrollable frustration it splattered those undeserving spines. And shame the hand that took the coin from my pocket and obliterated the waiter’s face upon the tin. In a witheringly disgraceful act of self-pitying pique I indelibly marked both, and regretted it bitterly within the second.

The sun has been kind to the Observer’s Books. Over the years it has faded the ink splatters on the spines, though the vestigial traces remain. No such mercy for the tin. It rests, scarred to this day, a lasting victim of youthful iconoclastic rage. And what was that rage; that yin to the yang of my usual calm self? To this day I have no recollection, no understanding of what she, he or it stirred me to this senseless act. But I stare though the thick lens of the ink bottle, and wish I could turn back time.