When war was declared in 1914 many young men in Britain were eager to enlist. This was the war to end all wars, the war that would be over by Christmas, the great adventure not to be missed. Some slipped through the net, and convinced the authorities they were of age, but most had to wait until their nineteenth birthday. Arthur, my paternal grandfather, eager to play his part, was one of those. He passed nineteen on 29th October 1914, and successfully enlisted one hundred years ago to this day, on 18th January 1915.

He spent his first few months in the British Expeditionary Force in Egypt, visiting Alexandria and Port Said, and returning with his head filled with romantic visions of Egypt and its people. But before long, and with bitter inevitability, the dark clouds loomed, and he was recalled to the main theatre of war, in northern France. Here he joined the Royal Field Artillery, and spent much time with the horses that pulled the guns. I cannot watch Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse without bittersweet memories of my grandfather’s recollections of those days, and his empathy for the poor creatures’ suffering. To this day we have his spurs, and this empathy rings true when I hold them, for on each he has replaced the spiked rowels with silver French coins. Amongst all that slaughter, horses had feelings too.

At some stage, and certainly by April 1917, he joined the Royal Engineers’ Corps of Signals, initially as a Signalman, and eventually as a Sapper. It was in this regiment that he spent the majority of the conflict, hunkered down in squalid conditions on France’s western front.

As with many men who endured the conflict, my grandfather spoke little of his experiences. But when he did he was inevitably drawn to fond reminiscences, and light-hearted anecdotes. We never learnt of the suffering and the pain, the unspeakable anguish of those young men. No. What I listened to, in my early years, were tales of him lying on his back in the sunshine of one calm afternoon, and watching a German red-painted tri-pane weaving overhead like a curious moth in search of nectar; or of the particular sound a shell makes as it streaks overhead. And my favourite tale of all, when, having cooked a pan of porridge in the board-lined dugout, he and his friends were intrigued to find lengths of string in their bowls as they ate, only to discover some time afterwards that their scant supply of candles had rolled from the shelf above, and fallen into the steaming pan. “Wax never did anyone any harm little man; it kept us insulated from the cold.” Always humour, always good grace, always humanity. He was always that way.

As with many men who endured the conflict, my grandfather spoke little of his experiences. But when he did he was inevitably drawn to fond reminiscences, and light-hearted anecdotes. We never learnt of the suffering and the pain, the unspeakable anguish of those young men. No. What I listened to, in my early years, were tales of him lying on his back in the sunshine of one calm afternoon, and watching a German red-painted tri-pane weaving overhead like a curious moth in search of nectar; or of the particular sound a shell makes as it streaks overhead. And my favourite tale of all, when, having cooked a pan of porridge in the board-lined dugout, he and his friends were intrigued to find lengths of string in their bowls as they ate, only to discover some time afterwards that their scant supply of candles had rolled from the shelf above, and fallen into the steaming pan. “Wax never did anyone any harm little man; it kept us insulated from the cold.” Always humour, always good grace, always humanity. He was always that way.

By God’s grace, or whatever providence looked over him, he came through the conflict, and married my grandmother in 1919. The same year he was stationed as part of the Army of Occupation in Germany. For a while he was billeted in Ramersdorf, in what he told us was Baron von Oppenheim’s castle. My father has a photographic postcard he sent to my grandmother, picturing the castle above the Rhine, and a pencilled arrow indicating “My room”.

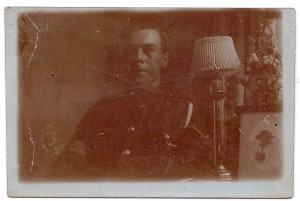

From Ramersdorf he was re-assigned to Köln, where he was billeted with a German family. For the rest of his life he spoke fondly of them, and never failed to express his gratitude for the friendliness and kindness with which the German people treated him, particularly his host family. We have a photograph of him from this time, sitting in his room in Köln. It’s a somewhat faded and indistinct image, but a compelling one nonetheless. What strikes me most when I look at it is the beguiling light in his eyes; eyes lit by optimism, by the prospect of a future life to be savoured. And the symbol of that optimism stands alongside him, in the framed photograph of my grandmother on his table; a photograph we still have.

From Ramersdorf he was re-assigned to Köln, where he was billeted with a German family. For the rest of his life he spoke fondly of them, and never failed to express his gratitude for the friendliness and kindness with which the German people treated him, particularly his host family. We have a photograph of him from this time, sitting in his room in Köln. It’s a somewhat faded and indistinct image, but a compelling one nonetheless. What strikes me most when I look at it is the beguiling light in his eyes; eyes lit by optimism, by the prospect of a future life to be savoured. And the symbol of that optimism stands alongside him, in the framed photograph of my grandmother on his table; a photograph we still have.

My memories of my grandfather are wholly benign. Each image I conjure belies the nature of the man. I see him perched high up on a ladder, painting the interior of his church. I see him mending clocks and watches for friends and family, a legacy of his father’s skills. I see him sitting at his table, watercolour painting; returning to images of the east, of Alexandria and the desert.

And certain phrases summon the memories like few others; act as a curious catalyst for fond reminiscences. Rise Up Like the Sun by the Albion Band is one of my favourite albums, and each time I listen to it my grandfather’s memory comes flooding back. The song Poor Old Horse not only re-awakens that empathy he had for the plight of the poor working horse, but contains one of the most evocative lines I know.

“He’s as dead as a nail in the lamp room floor” it goes, and each time I hear it the involuntary impulse drives me back, back to my childhood, back to a way of life long gone, back to him. The words are in all probability lost on many. But to me the lamp room floor is a compellingly evocative image. After the war my grandfather, newly married, relocated from his native Isle of Wight to Yorkshire, the county of my grandmother’s birth. For those men that survived the war, the collieries promised a trade, a livelihood, which exerted an irresistible attraction. And so his life played out, amidst the grime, the danger, but significantly the fiercely proud companionship of the collieries. He remained there for the rest of his working life. When I was a small child I remember being taken to see him at Ackton Hall colliery in Featherstone. And my two lasting memories of that visit were of the leviathan of a winding engine, and the curiously Victorian ambiance of the lamp room, where the miners’ lamps were maintained and re-primed.

As dead as a nail in the lamp room floor; I’ve trod those ancient boards. And in my imagination I still do, with Arthur at my side.